Lighthouses

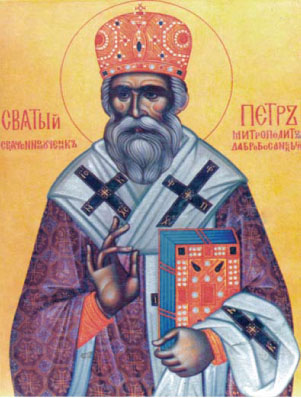

SAINT PETAR ZIMONJIĆ (1866-1941), METROPOLITAN OF DABAR AND BOSNIA

Dedication through Temptations

He hasn’t been given peaceful and blissful times, but he had everything a true Christ’s soldier needs in times completely different from the wished ones. Because of his nobleness and goodness, he has indeed been beloved, which executioners rarely forgive. It remains unknown whether he ended his life in Jadovno, Jasenovac or Zagreb, but it is known that he suffered for the sake of the Godman

By: Hristina Plamenac

St. Petar Zimonjić belongs to the most educated and greatest arch-shepherds of his time. Despite this, little has been spoken or written about this life, while his death has remained a mystery up to the present day.

He was born on June 24, 1866 in Grahovo, as the youngest son of Mara and Bogdan Zimonjić, priest and duke in Herzegovina. After finishing the Reljevo Seminary, (1883-1887), he enrolled at the Orthodox Seminary Faculty in Chernovitz (in present-day Ukraine), the highest educational institution of its kind in Austro-Hungary. After completing his studies (1887-1893), he spent a year at the Vienna University, and was later appointed professor of the Reljevo Seminary, where he was a distinctive and extraordinary pedagogue. As a professor, he entered the monastery of Žitomislić in 1895 (September 6).

FOLLOWING THE FOOTSTEPS OF VASILIJE OF OSTROG

Six years later, in 1901, he became the consistorial advisor of the Archbishopric of Dabar and Bosnia, where he was elected Metropolitan of Zahumlje and Herzegovina. After hearing that the bishop is arriving by train, about 4.000 souls gathered at the station, including Muslims and Catholics. Old (ninety-one year old) duke Bogdan was also at the station, not to greet his son, but his bishop.

All the deepness of St. Peter’s gentle and dignified personality may be seen in his salutary speech. For, indeed, he was one of those people whose deeds speak best of them, by which we can recognize them best.

”What shall I say to you, my dear kindred, from which I have sprouted and to whom I owe so much? I would most rather enjoy with you and have long conversations. I would have reason both to scold and to praise you. But I shall not praise you, since I am afraid I would hurt your pride with such words; I shall also not scold you, since then there is nothing to praise myself with…”

He found disorder in the eparchy. A series of tragic historical events soon followed. First, all hopes for liberation were lost after the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Then followed the Balkan Wars, and then World War I started with the prosecution and killing of priests in B&H. During this time, the Metropolitan, as any caring father, did everything possible and impossible for his people, earning respect during his lifetime, similar to his great predecessor St. Vasilije of Ostrog and Tvrdog. Despite the difficult times and fear that such times provoked, St. Petar managed to raise and restore churches, and to ordain priests. During his time, the Metropolitan Court in Mostar was built (burnt down by the Croatian paramilitary units in 1992).

After the war ended, he comprehensively worked on uniting the Serbian Orthodox Church, and then, after the establishment of the Patriarchy, upon the request of the Church, in 1920 he was transferred to the Archbishopric of Dabar and Bosnia lectureship. If there had been any animosity and hostility after World War I, the bishop did much to end the hostilities, tensions and distrust, and to heal the wounds of war. He often went for walks through the Muslim suburb. Seeing him come, people would come out of their shops and coffee shops and greet him with respect.

HOPES AND HERALDS OF TEMPESTS

After the death of Patriarch Varnava (poisoned during the most extreme fights over the concordat), St. Petar was one of the candidates for Patriarch. Besides him, Gavrilo Dožić and Georgije Zubković were also suggested to the royal officials. Gavrilo Dožić was elected as Patriarch.

During the times when Petar Zimonjić was arch-shepherd of the Archbishopric of Dabar and Bosnia, the people began attending liturgies regularly, took an active part in building temples, schools were opened, a Children Home and Kitchen for the Poor. One of the last reports of the Metropolitan to the Holy Archpriest Synod testifies about all this.

Then began World War II and the bombing of Sarajevo on Holy Wednesday in 1941. The Metropolitan was evacuated to the Monastery of Holy Trinity near Pljevlja. Although he knew that his eventual return would mean certain death, his fatherly care for his people still took him back to Sarajevo, on the second day of Easter.

A week after came the German officers for inquest. They accused the elderly bishop for all sorts of things and threatened him. The bishop, as a man respecting others and always defending his own, politely replied:

”Sir, you are very wrong, we are not to blame for the war, but we will not allow to be killed. I do not fear of death threats, since I am already with one foot in my grave.”

A few days later, the Ustasha delegate in Bosnia, the Roman-Catholic parson of Sarajevo Božidar Brale, contacted him and asked him to order the clergy not to write in Cyrillic letters any more and to replace the Cyrillic seals with the Latin alphabet, since the Cyrillic alphabet has become illegal in NDH (Independent State of Croatia). The chronicles state that the Metropolitan’s reply was short:

”Cyril’s alphabet cannot be canceled in 24 hours.”

Then Brale asked him to repeat it to his commissioner for education Vučko, which the Metropolitan did. As, besides everything, he also refused to hold a gratitude service for Pavelić, he expected them to come any moment and take him away.

TORTURING PLACES AND SCAFFOLDS

That very thing happened on May 12, 1941 (on the day of St. Vasilije). The Ustasha police agents came and took him to the police station. Then he was transferred to the ”Beledija” general prison. He was completely isolated, and it was impossible to make any contact with him.

Three days later, two agents brought the bishop back to, allegedly, take what he needs. They also ordered the safe to be opened, and they took the panagias, medals and documents. (Decades later, the Metropolitan of Dabar and Bosnia Vladislav, during his business trip to Zagreb, found a protocol with the list of things which were taken. Of all the things, only those which could not be sold remained: diplomas and decrees about the medals).

The bishop was taken to Zagreb and put in a police prison under file number 29781. From there he was transferred to the ”Kerestinac” camp where he was cruelly tortured and maltreated. When the camp was dissolved on June 15, the Metropolitan was taken to the Ustasha camp in Gospić. The torturing, derision and humiliation continued. He was taken out in the most terrible rain shower to, alone in the yard, ”preach as he used to preach to the Serbs in Sarajevo”. Reconciled and brave, as a true soldier of Christ, carrying his wreath of thorns, he began each sermon with: ”Dear God…”

He disappeared without trace in Gospić. The Serbian Orthodox Church attempted in every way to find something out about Metropolitan Petar and Episcope of Gornji Karlovac Sava. They received a response that they were in none of the concentration camps in NDH. During 1942, ”a story came out” that the bishop has a disease of the nerves and that he is ”taken care of in the hospital in Stanjevac, Zagreb”. The Metropolitan of Skopje Josif, who (in the absence of the imprisoned Patriarch Gavrilo) presided over the Holy Archpriest Synod, asked the government president Milan Nedić to find something out about the Metropolitan from the German authorities. The reply stated that ”his residence could not be determined”.

In 1998, at the regular session of the Serbian Orthodox Church Holy Archpriest Synod, he was proclaimed as a holy martyr and ”joined the other holy ones from the Serbian nation and of Christian-Orthodox faith. The Serbian church celebrates him in the third week of September…”

***

Three Versions of Death

Presently there are three versions of Metropolitan Petar’s death. First: he was taken to Koprivnica from Gospić, and then to the Zagreb hospital in Stanjevac, where he was killed. Second: he was taken to the camp in Jadovno, on Velebit, and thrown into the Šaran’s pit – the largest known scaffold of Serbs. According to the third version, he was killed in Jasenovac and ”thrown into the flaming furnace for baking brick”. In any case, it is certain that he suffered and died as a martyr for Christ.

***

Unforgivable

Metropolitan Petar Zimonjić did what no one before or after him was able to do in B&H – he calmed down the passions and eliminated misunderstandings. He was truly loved among the people. But the way he taught and acted in such an evil and unscrupulous time, and in such a space, was unforgivable.